Flux is an application architecture designed by Facebook for their JavaScript applications. It was first introduced by Facebook in May 2014, and it has since garnered much interest in the JavaScript community.

There are several implementations of Flux. Frameworks like Fluxxor keep to the original Facebook Flux pattern, but reduces the amount of boilerplate code. While other frameworks like Reflux and Barracks stray from the canonical Flux architecture by getting rid of the Dispatcher (Reflux) or ActionCreators (Barracks). So which framework should you choose?

Before we get too wrapped up about what is canon, and whether we should be deviating from them, let’s consider a look into the past.

While the Flux pattern may have found a new home in JavaScript applications, they have been explored before in Domain-Driven Design (DDD) and Command-Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS). I think it is useful to learn from these older concepts, and see what they may tell us about the present.

In this post I will:

- Give an overview of the Flux architecture.

- Present the CQRS pattern.

- Look at how Flux applies the concepts from CQRS.

- Discuss when Flux is useful for a JavaScript application.

Knowledge of DDD is assumed, though the article still provides value without it. To learn more about DDD, I recommend this free ebook from InfoQ on the subject.

Examples will be shown in JavaScript, though the language isn't the focus of this post.

What is Flux?

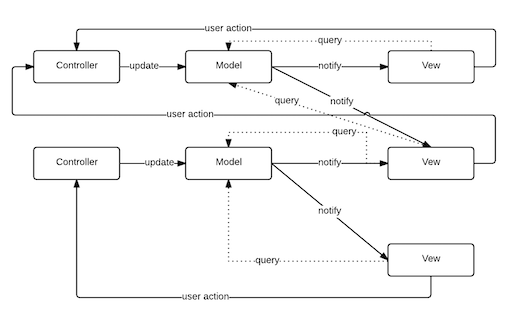

A common way to describe Flux is by comparing it to a Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture.

In MVC, a Model can be read by multiple Views, and can be updated by multiple Controllers. In a large application, this results in highly complex interactions where a single update to a Model can cause Views to notify their Controllers, which may trigger even more Model updates.

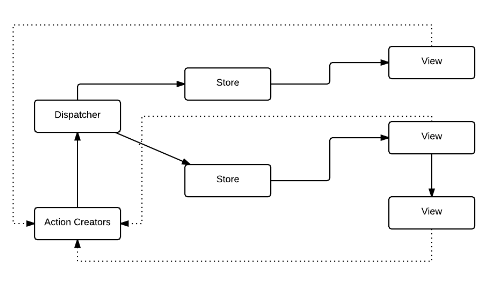

Flux attempts to solve this complexity by forcing a unidirectional data flow. In this architecture, Views query Stores (not Models), and user interactions result in Actions that are submitted to a centralized Dispatcher. When the Actions are dispatched, Stores can then update themselves accordingly and notify Views of any changes. These changes in the Store prompts Views to query for new data.

The main difference between MVC and Flux is the separation of queries and updates. In MVC, the Model is both updated by the Controller and queried by the View. In Flux, the data that a View gets from a Store is read-only. Stores can only be updated through Actions, which would affect the Stores themselves not the read-only data.

The pattern described above is very close to CQRS as first described by Greg Young.

Command-Query Responsibility Segregation

To understand CQRS, let’s first talk about the object pattern Command-Query Separation (CQS).

CQS at an object level means:

- If a method mutates the state of the object, it is a command, and it must not return a value.

- If the method returns some value, it is a query, and it must not mutate state.

In normal DDD, Aggregate objects are used for both command and query. We will also have Repositories that contain methods to find and persist Aggregate objects.

CQRS simply takes CQS further by separating command and query into different objects.

Aggregates would have no query methods, only command methods. Repositories would

now only have a single query method (e.g. find), and a single persist method

(e.g. save).

In the CQRS pattern, you will find new objects not found in normal DDD.

Query Model

The Query Model is a pure data model, and is not meant to deliver domain behaviour. These models are denormalized, and meant for display and reporting.

Query Processor

Query Models are usually retrieved by performing a query. The queries can be handled by a Query Processor that knows how to look up data, say from a database table.

Command Model

Command Models are different from normal Aggregates in that they only contain command methods. You can never “ask” it anything, only “tell” (in the Tell, Don’t Ask sense).

As a command method completes, it publishes a Domain Event. This is crucial for updating the Query Model with the most recent changes to the Command Model.

Domain Event

Domain Events lets Event Subscribers know that something has changed in the corresponding Command Model. They contain the name of the event, and a payload containing sufficient information for subscribers to correctly update Query Models.

'ITEM_ADDED_TO_CART').

Event Subscriber

An Event Subscriber receives all Domain Events published by the Command Model. When an event occurs, it updates the Query Model accordingly.

Command

Commands are submitted as the means of executing behaviour on Command Models. A command contains the name of the behaviour to execute and a payload necessary to carry it out.

AddItemToCart).

Command Handler

The submission of a Command is received by a Command Handler, which usually fetches an Command Model from its Repository, and executes a Command method on it.

An example in e-commerce

Let’s compare normal DDD with CQRS in the context of an e-commerce system with a shopping cart.

Shopping cart with normal DDD

In normal DDD, we may find an Aggregate ShoppingCart that contains multiple CartItems,

as well as a corresponding Repository.

// The Aggregate model

class ShoppingCart {

constructor({id: id, cartItems: cartItems, taxPercentage: taxPercentage,

shippingAndHandling: shippingAndHandling}) {

this.id = id;

this.cartItems = cartItems || [];

this.taxPercentage = this.taxPercentage;

this.shippingAndHandling = shippingAndHandling;

}

// Command methods

addItem(cartItem) {

this.cartItems.push(cartItem);

}

removeItem(cartItem) {

this.cartItems = cartItems.filter((item) => item.sku !== cartItem.sku);

}

// Query method

total() {

var prices = this.shoppingCart.cartItems.map((item) => item.price);

return prices.reduce((total, price) => total + price, 0);

}

}

// A child of the Aggregate

class CartItem {

constructor({sku: sku, description: description, price: price, quantity: quantity}) {

this.sku = sku;

this.description = description;

this.price = price;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

}

// Repository to perform CRUD operations

class ShoppingCartRepository {

all() { /* … */ }

findById(id) { /* … */ }

create(cart) { /* … */ }

update(cart) { /* … */ }

destroy(cart) { /* … */ }

}Here, the ShoppingCart is responsible for both queries (cartItems andtotal()),

and updates (addItem(), removeItem(), and normal property setters). The

ShoppingCartRepository is used to perform CRUD operations on ShoppingCart.

Shopping cart with CQRS

In CQRS, we can do the following:

-

Convert the

ShoppingCartinto a Command Model. It would not have any query methods, only command methods. It also has the extra responsibility to publish two Domain Events ('CART_ITEM_ADDED','CART_ITEM_REMOVED'). -

Create a Query Model for reading the shopping cart total (replacing the original

.total()method). This Query Model can simply be a plain JavaScript object.

{

cartId: 123,

total: 129.95

}

-

Create

CartTotalStorethat holds the query models in memory. This object acts like a Query Processor in that it knows how to look up out Query Models. -

Create an Event Subscriber that will keep out Query Models updated whenever Domain Events are published. In this example we will assign this extra responsibility to the

CartTotalStore, which is easier and closer to what Flux does. -

Create a Command Handler

ShoppingCartCommandHandlerin order to execute behaviour on the Command Model. It will handle bothAddItemToCartandRemoveItemFromCartCommands.

Note: We are creating a Command Handler that is responsible for multiple Commands. In practice, we may choose to create one handler for each command.

// The Command Model publishes Domain Events.

class ShoppingCart {

constructor(/* … */) {

// …

}

addItem(cartItem) {

// …

DomainEventPublisher.publish('CART_ITEM_ADDED', {

cartId: this.id,

sku: cartItem.sku,

price: cartItem.price,

quantity: cartItem.quantity

});

}

removeItem(cartItem) {

// …

DomainEventPublisher.publish('CART_ITEM_REMOVED', {

cartId: this.id,

sku: cartItem.sku,

price: cartItem.price,

quantity: cartItem.quantity

});

}

}

// This object acts as both the Query Processor and Event Subscriber.

class CartTotalStore {

constructor() {

// Holds Query Models in memory.

this.totals = {};

// Subscribe to events that allows this store to update its Query Models.

DomainEventPublisher.subscribeTo('ITEM_ADDED_TO_CART', this.handleItemAdded);

DomainEventPublisher.subscribeTo('ITEM_REMOVED_FROM_CART', this.handleItemRemoved);

}

// Query method

forCart(cartId) {

return {

cartId: cartId,

total: this.totals[id]

};

}

// Methods to update Query Models.

handleItemAdded({cartId: cartId, cartItem: cartItem}) {

var total = this.totals[cartId] || 0;

var newTotal = total + cartItem.price * cartItem.quantity

this.totals[cartId] = newTotal;

}

handleItemRemoved({cartId: cartId, cartItem: cartItem}) {

var total = this.totals[cartId] || 0;

var newTotal = total - cartItem.price * cartItem.quantity

this.totals[cartId] = newTotal;

}

}

// This Command Handler maps Commands to command methods ShoppingCart.

class ShoppingCartCommandHandler extends CommandHandler {

constructor(repo) {

this.repo = repo;

// Assumes commands implement subscribe that appends the handler to themselves.

AddItemToCart.subscribe(this.addItemToCart);

RemoveItemFromCart.subscribe(this.removeItemFromCart);

}

addItemToCart(payload) {

var cart = this.repo.find(payload.cartId);

cart.addItem(payload.cartItem); // This publishes a Domain Event

}

removeItemToCart(payload) {

var cart = this.repo.find(payload.cartId);

cart.removeItem(payload.cartItem); // This publishes a Domain Event

}

}You should now have an understanding of CQRS. Next, we will examine how Flux relates to CQRS.

Flux and CQRS

Let’s see how the different types of object in Flux map to the CQRS pattern.

Actions

Actions are exactly the same as Domain Events. They should represent events that have happened in the past, and will cause updates to Query Models in the system.

Dispatcher

The Dispatcher is the Domain Event Publisher. It is a centralized place where Actions are published to. It also allows Stores to subscribe to Actions that are published in the system.

Stores

Stores listen for Actions published through the dispatcher, and update themselves accordingly. In CQRS, they would be the Event Subscriber.

In addition to being the Event Subscribers, they also act as Query Processors.

This is intentionally similar to our implementation of CartTotalStore. In some

CQRS systems, however, the Event Subscriber and Query Processor may not be the same

object.

ActionCreators

ActionCreators are the Command Handlers. In this case, though, submitting Commands just means calling methods on the ActionCreator. As opposed to having Commands exist as a separate object.

e.g. ShoppingCartActionCreators.addItem(…)

As you see, the canonical Flux architecture is only one way of implementing CQRS in a system. It also adds a lot of objects into a system, compared with a normal DDD approach. Is added bloat worth it?

When should I Flux?

I don’t think this architectural pattern is appropriate for all situations. Like other tools under our belt, don’t use mindlessly apply the same patterns everywhere.

In particular, Flux may be inappropriate if your views map well to your domain models. For example, in a simple CRUD application, you may have exactly three views for each model: index, show, and edit + delete. In this system, you will likely have just one controller and one view for each CRUD operation on your model, making the data flow very simple.

Where Flux shines is in a system where you present multiple views that don’t map directly to your domain models. The views may be presenting data aggregated across multiple models and model classes.

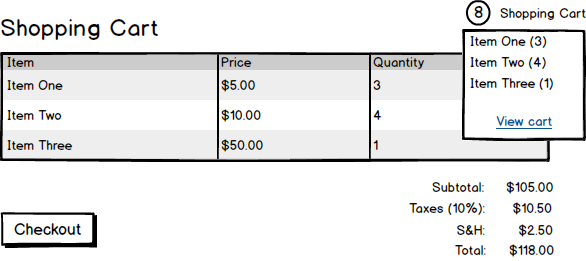

In our shopping cart example, we may have:

- A view that lists out items in the cart.

- A view that handles displaying subtotals, taxes, shipping & handling, and totals.

- A view that displays amount of items in cart, with a detailed dropdown.

In this system, we don’t want to tie different views and controllers directly to a ShoppingCart model because changes to the model causes a complex data flow that is hard to reason about.

Closing thoughts

As you have seen, we can think about the canonical Flux architecture in terms familiar in CQRS.

There are several object roles in CQRS.

- Query Model

- Query Processor

- Command Model (Aggregate)

- Commands

- Command Handler

- Domain Event

- Domain Event Publisher

- Event Subscriber

In Facebook Flux some objects take on more than one role. This is perfectly reasonable to do! When we encounter other Flux implementations, we could also discuss them using the different object roles in CQRS.

Does this mean we should buy books and materials about CQRS and become experts on that? Not necessarily. But I think it is interesting to see how some of these old concepts are becoming new again.