As programmers, one of the most important skills to have is being able to learn quickly. It doesn’t matter that you know frameworks X and Y, or languages Foo and Bar. what’s hot and what’s not will change several times throughout our career, but the skill to learn new abilities will always be in demand.

In this post, I want to look at what it takes to be a good learner, as well as some techniques we can employ to help us along the way.

The Purpose Of Learning

We face many problems everyday. Some problems are technical in nature, while others could be business problems, social problems, etc. Picture a big problem space that consists of all the problems we could solve. The act of learning expands our solution space, which in turn may lead to solutions for our problems.

When a solution is missing, it is our responsibility to learn it.

Start By Setting The Right Goals

There are two classes of goals we can have when we learn.

- Performance goals, in which individuals are concerned with how well they perform at a task. Individuals may set these goals to gain favourable judgement of their competence.

- Learning goals, in which individuals are concerned with increasing their competence.

Dr. Carol Dweck has done research that shows that people with performance goals tend to view the amount of effort exerted in learning as an indicator of their ability [1]. Exerting high amount of effort means an individual has low ability. Even more dangerous, these individuals view failures as warning signs that they will be judged as having low ability. Therefore when high effort is required, these individuals may experience anxiety.

Compare this to people with learning goals, who view effort as a means of activating ability. These individuals also view failures simply as an indication that the task will require more effort. As well, exerting effort in the service of learning may bring intrinsic rewards and pleasure.

We should try to prioritize learning goals over performance goals. That is not to say that performance goals are bad. What is important is our attitude when faced with failures. Do not take failures as an indication of personal deficiencies, but rather as a signal to put more effort in. We also need to keep our original performance goal in view and develop a proper strategy to meet that goal.

So how do we deal with challenges when reaching for our goals?

Using Adversity

The fact of the matter is that there will be nothing learned from any challenge in which we don’t try our hardest. Growth comes at the point of resistance. We learn by pushing ourselves and finding what really lies at the outer reaches of our abilities. Josh Waitzkin, The Art of Learning

When faced with adversity, there are two mindsets that can determine whether individuals are successful in overcoming said adversity.

-

The helpless mindset is one in which individuals believe that intelligence is a fixed trait. That is, you cannot increase the amount of intelligence you have. This leads to a maladaptive pattern that deters individuals from confronting obstacles or prevents them from functioning effectively in the face of difficulty.

-

The mastery-oriented mindset is one in which individuals think intelligence is malleable and can be developed through education and hard work. This leads to an adaptive pattern that helps maintain a commitment to their goals through periods of difficulty.

In Dr. Dweck’s research [1], she found that during the onset of failures, children who exhibit the helpless pattern tend to experience anxiety over their performance. They attributed the failures to personal deficiencies, and much of them used diversionary tactics to bolster their own ego. For example, they may trivialize the task at hand, or talk about how good they are in other things. These “helpless” children also tend to view further effort as futile, as the task is beyond their ability.

With mastery-oriented children, the obversation is that they did not give attributions for their failures. They viewed unsolved problems as a challenge to be conquered through hard work. They relished the opportunity to reach a solution.

These same patterns have been observed in adults as well.

The takeaway here is that when we face challenges, we should focus on mastery through strategy and effort. Do not let pride and ego get in the way of an opportunity to learn.

So what are some strategies we can employ to help us on our endeavours?

Spaced Repetition

Everything we learn in our lifetime has an expiry date. Although you may not have realized it, that calculus you learned in school years ago is probably not within your current abilities – unless you’ve practiced it recently.

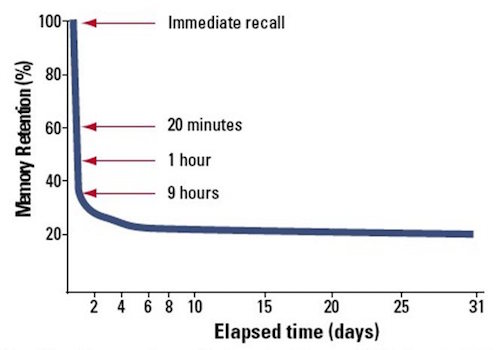

This phenomenon has been documented in research by psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. He found that your chance of memory retention goes down drastically after the first few hours, then slowly declines after a few days.

All is not lost though, because we can employ a technique known as spaced repetition to combat this memory decay.

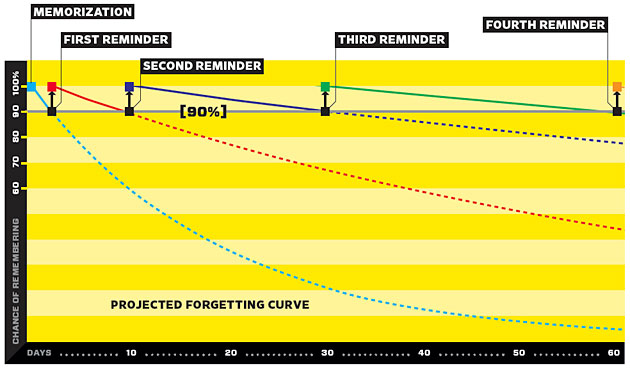

This technique reinforces what we have learned through review of the material in increasing intervals of time. After our initial memorization of the material, we need a reminder of the material soon after in order to have a good chance of remembering it. The second reminder will then follow a longer period of time compared to the first. And the third reminder comes after an even longer period of time, and so on.

Spaced repetition has been shown in a study by H.F. Spitzer to be effective. [2]

In practice, we need to first recognize the materials we want to remember. Once we know what we want to remember, we need to set periodic reviews of those materials. For things that we have just learned, we need to do our reviews at least within the first couple of days, then we keep up the reviews with increasing intervals of time.

The implication here is that we need to dedicate time to revisit materials in addition to learning new materials. The corollary is that we should be explicit about the things we are okay with forgetting, and stop review those things.

Learn All The Things

Half-a-skill beats a half-assed-skill. Kathy Sierra

As we increase the breadth of our knowledge, we invariably decrease our depth in some. Imagine a full-stack developer, whose knowledge spans from backend Rails code, to various database systems, to a bunch of JavaScript frameworks. This full-stack developer may lack knowledge in certain parts of the Rails ecosystem, or may not know exactly how parts of AngularJS work.

Now, compare this to a specialist developer, who may know the ins and outs of building a Rails backend, but cannot write a single line of JavaScript code.

Which is better? Can’t we just learn all the things?

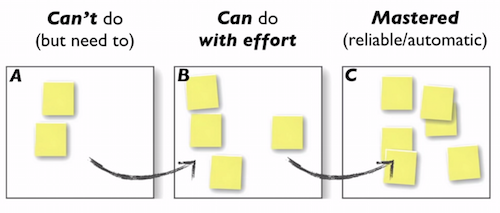

In a talk by Kathy Sierra called Making Badass Developers, she talks about having three categories of skills.

- Things we can’t do, but need to.

- Things we can do with effort.

- Things we mastered and can do reliably with little effort.

You can picture learning as moving things from A to B, and from B to C.

One of the problems that Kathy identifies is that people let way too many items pile up on B. That is, we have a bunch of skills that we think we need, but we have to exert tremendous amounts of effort everytime we access that those skills.

An easy solution for this is to move things back to A. We can be explicit about not learning a skill, and free up our cognitive resource to pursue other skills. This option is great if it is actually available to us. The reality is that we might not have a say in what skills we need for our jobs.

The other solution (perhaps a more viable one) that Kathy proposes is to break a skill down to many sub-skills. For example, instead of mastering all of Rails, I might spend my efforts in learning Arel really well because I find myself needing that knowledge quite often at work. I can further break “Rails” downs into smaller skills, such as knowing how Active Records work, how Nokogiri works if I’m dealing with XML a lot, etc.

And what about AngularJS? Do I really need to completely master directives, or can I get away with just knowing how to wire up services and controllers?

Be cognizant of how the skills or sub-skills we spend our efforts on actually tie back to our learning or performance goals. Also keep in mind that any skils we acquire will have to be practiced over and over again using spaced repetition.

Now, one other problem that Kathy identifies is that even once we’ve identified that we need to take a skill from A to C, it might take us too long to get there. This is where the deliberate practice comes in.

Deliberate Practice

Expert performance is qualitatively different from normal performance and even that expert performers have characteristics and abilities that are qualitatively different from or at least outside the range of those of normal adults. However, we deny that these differences are immutable, that is due to innate talent. Only a few exceptions, most notably height are genetically prescribed. Instead, we argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain. K. Anders Ericsson

Just to recap, so far we have discovered:

- Setting learning goals and having a mastery-oriented mindset helps us be successful in out learning endeavours.

- In order for us to retain a skill that we have learned, we need utilize spaced repetition.

- It is better to break a widely-scoped skill down to sub-skills so we can master a subset of those sub-skills.

The last piece of the puzzle is how we go about learning these smaller sub-skills in an efficent manner. According to research by K. Anders Ericsson, the difference between the “expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain.” [3]

According to Ericsson, there are four components of deliberate practice. [3]

-

You must be motivated to attend to the task and exert effort to improve your performance.

-

Each task should be designed to take into account your pre-existing knowledge. This will ensure the task is correctly understood after a relatively brief period of instruction.

-

You should receive immediate informative feedback and knowledge of results of your performance.

-

The same or similar tasks should be performed repeatedly.

Component #1 is basically having the right mindset and goals when we are learning a skill. Component #4 points back to spaced repetition.

What we haven’t discusses so far are components #2 and #3.

Accounting For Pre-Existing Knowledge

Imagine telling a beginner pianist to learn to play Moonlight Sonata Movement 3. No matter how dedicated that pianist is to practice, they will never be able to play it because they currently lack the knowledge and skills required to even begin to tackle that piece of music. It is much more fruitful to break that goal of playing Moonlight Sonata Movement 3 into smaller, more attainable tasks, with increasing difficulty. For example, as the pianist I may need to first practice my techniques (scales, chords, etc.) in order for my fingers to be able to handle playing at such speeds. The techniques I need to master will start with more basic ones that I can reasonably achieve in the short term. Then as time passes, I will crank up the difficulty and complexity. Eventually, I will have enough techniques under my belt that playing this Sonata will be realistic.

The same is true for programmers. There is no way a junior programmer can learn how to build a distributed, event-driven system from scratch. Sorry to burst your

bubble, but no amount of Stackoverflow answers will help you. There is no framework you can npm install that will help you.

You first need to learn the basics of distributed computing. Build a few distributed systems. Then learn about event-driven architecture. Build a few systems in that architecture. Then think about all the glue pieces between distributed and event driven systems. Do I need to learn CQRS? Do I need to guarantee total ordering of events? If so, what techniques can I apply to achieve this? Do I need to learn more about asynchronous architectures? What else do I need to know?

We need to ensure we can get to the next step of our goal using the knowledge we currently possess. You cannot go from A to B if you cannot understand what B is. It is better to modify our plan to go from A to B, from B to C, from C to D, and so on, as long as each step is attainable using what we’ve learned in the previous step.

Receiving Feedback Of Your Performance

So now we have a practice plan designed for our current skill level. But how do we know we’ve attained the next level in our learning goal? The only way to tell is if we get immediate feedback that we understand what we’re trying to learn.

For example, personally for me I have small toy apps that I keep re-implementing in different frameworks, languages, and architectural patterns. Why? Because once I can build the app in a new language, I know that I’ve achieve a basic understanding of that language. Same thing for frameworks and architectural patterns. This is both deliberate (I want to achieve basic understanding of X) and measureable (I’ve succeeded once I can build this without looking at Stackoverflow).

The one thing I will caution about measuring feedback is to limit the number of variables you have. Don’t try to learn ReactJS frontend and Django backend all in the same session. You will never get good feedback by doing that. Be very deliberate about what you want to achieve, and devise a plan that only tackles those goals.

Conclusion

As programmers, learning is something we have to do repeatedly over the course of our career. In order to achieve the best results, it is important to make sure we have the right mindset and set the right goals for ourselves.

If possible, use learning as a goal in and of itself. Don’t let ego prevent us from learning in the face of adversity.

Be explicit about the skills you want to retain. Keep praticing those skills because you will forget them otherwise.

If a skill is too big to learn, try breaking it down into smaller sub-skills and master those.

Once you’ve identified those sub-skills, be very deliberate about how you can learn them using your existing knowledge, and think about how you can collect feedback in your learning sessions.

I hope this post has been helpful to you. Have fun learning!

I’d like to thank Chris Wu for his help editing this post and the suggestion to include deliberate practice.

References and Resources

- [1] Dweck, Carol and Leggett, Ellen L. (1988). A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality

- [2] Spitzer, H. F. (1939). Studies in retention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 30, 641–657

- [3] Ericsson, K. Anders (1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance

- Kathy Sierra - Making Badass Developers (video)

- Edward Kmett - Stop Treading Water: Learning to Learn (video)

- Deliberate Practice: What It Is and Why You Need It

- The Grandmaster in the Corner Office: What the Study of Chess Experts Teaches Us about Building a Remarkable Life

- The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance (book)