Dynamically typed languages like JavaScript provide a lot of expressiveness and power to the programmer. By not having to think about strict types, a program is more maleable since it will run no matter what, allowing the programmer to write code very quickly.

The problem with dynamic types is that it slows down development of an application over time. This decrease in velocity can be attributed to a couple of factors.

-

Bugs introduced by type mismatches (such as

nulltypes) take time away from feature development. -

Each time existing code is examined, the programmer needs to figure out what the intended types are again.

But Why Worry About Types At All?

Programs should be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.

- Abelson and Sussman in “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs”

The first question you may ask is why we should bother with types at all? The answer to this is simple: Types are like the weather. There is nothing you can do about it. Weather happens.

Whenever you write down JavaScript code, you are already thinking about types, just unable to write them down.

For example, say you implemented an add function as follows.

const add = (a, b) => a + bThe types for a and b are implicitly number, but there is no way to write this down in code.

Or how about a greet function as follows.

const greet = (name = 'World') => console.log(`Hello ${name}!`)Can you guess the type for the parameter name? If you guessed string then you are close but not quite

correct. The correct type is an optional string – meaning it can be undefined.

Without explicit types, we will inevitably make a mistake and use the wrong ones. Is add(null, 2) a valid invocation? Obviously not!

But what about add('1', 2). Maybe? It is hard to know the original intention of the function’s author.

In short, it is very difficult for another programmer (or the future you) to understand what the originally intended types are for every function in an application.

Types To The Rescue!

Let’s look at both functions again with type declarations (using Flow).

const add = (a: number, b: number): number => a + b

// `name?` means it is optional

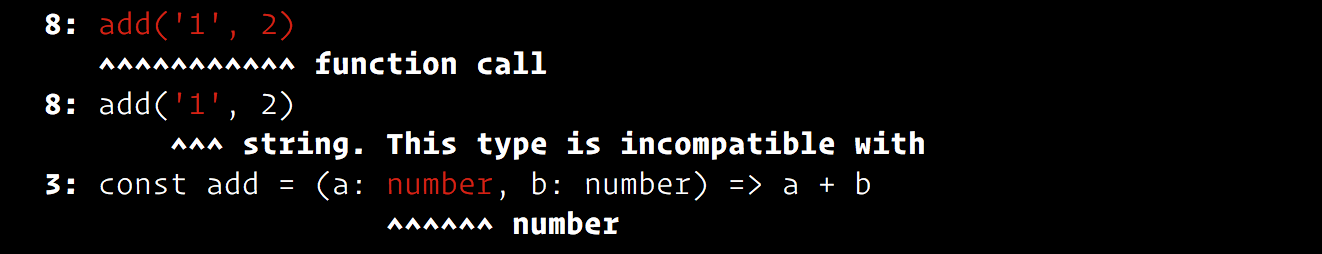

const greet = (name?: string = 'World'): void => console.log(`Hello ${name}!`)It is now clear that add('1', 2) is not a valid invocation of the function. Furthermore, the Flow

type checker will actually throw a useful error.

(We also know that add(add(1, 2), 3) is valid, because the return type of add is number!)

As for the greet function, it should be clear which of the following statements are valid or not.

greet() // Valid with since name is optional

greet('Alice') // Valid since 'Alice' is a string

greet(1) // Invalid since 1 is not a string

greet(null) // Invalid since null is not a string

add(greet(), 2) // Invalid since greet returns void, which is not a numberGetting Rid Of That Dreaded Null error

The single most common error in a JavaScript application is likely the null is not a function error, or some variation of it.

This class of error is completely due to type mismatches: Not dealing with nullable types properly.

For example, given a function such as the following.

const updateEmail = (person, email) => {

person.contact.email = email

}It isn’t clear whether there is a bug in that code or not.

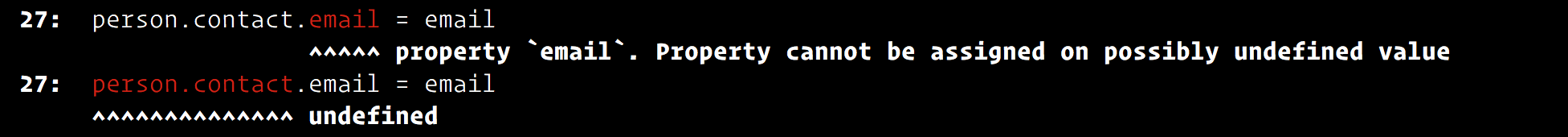

However, if I were to add some type annotations to it, then it is very clear that there is a bug!

type IPerson = {

id: number,

contact?: {

email: string,

address: string

}

}

const updateEmail = (person: IPerson, email: string): void => {

// `contact.email` may be undefined, thus is unsafe!

person.contact.email = email

}In fact, you don’t even need to manually check the code since Flow will check for you.

Awesome!

Aren’t Types Too Constraining and Troublesome?

There are two common concerns of using a type system:

-

They are too troublesome to set up.

-

They constrain the programmer too much.

While both are valid concerns, Flow type – and TypeScript to some extent – provide an almost seemless experience.

For starters, if we take the original add function, and simply add the // @flow comment to the module,

then we can already run it through the type checker!

// @flow

const add = (a, b) => a + bOf course, without type annotations, the type checker is limited in usefulness. It can catch errors such as

add([], 2) but not add(null, 2), since the latter null + 2 operation is (unfortunately) valid JavaScript.

add function:

e.g. add(1) and add().

As for contraints caused by static types, it simply isn’t true. If you want dynamism, you can

use the any type to forgo type checking. In fact, the any type is implicitly the only type available

in pure JavaScript!

// @flow

const add = (a: any, b: any): any => a + b

add(null, null) // Valid

add() // Valid

add([], {}) // Valid

add(add, add) // ValidAdding Types To Your Project Today!

Now that I’ve convinced you that types are really great, then the next step is setting it up in your own

project. I recommend Flow if want to perform a quick experiment, since the set up is faster than the alternatives.

TypeScript is also great, but it will require a bit more work (e.g. configuring tsconfig.json and renaming .js

files to .ts). In a real project you will need to weigh the pros and cons of each technology choice.

Setting Up Flow

You only need to do two things to get Flow running in your project.

Firstly, install the flow binary globally.

npm install -g [email protected]

Secondly, go to your project root and run:

flow init # This creates the .flowconfig file

That’s it! You can now verify that Flow is working in your project.

flow check

This should produce no errors since you have not added the // @flow comment to any modules yet.

Gradually Adding Types

The next step is to start adding types to your modules. I recommend starting with modules that don’t have any dependencies (i.e. no imports), or as little imports as possible. If a module has dependencies, then you will need to type those first before typing the dependent module.

If you are working with third-party modules, you will need to install those type definitions

before you can import them. The best way to get third-party type definitions is using flow-typed.

npm install -g flow-typed

You can search and install type definitions using this binary.

flow-typed search redux

flow-typed install -f 0.30 redux

The -f option specifies the Flow version you want to install the definition for.

To automatically include the installed definitions, add an entry to the [libs] section in the .flowconfig file.

[libs]

./flow-typed/npm/

If you cannot find type definitions using flow-typed , you can simply provide them yourself.

Start by adding a new [libs] entry to the .flowconfig file.

[libs]

./flow-typed/npm/

./manual-typings/

Then define the third-party modules in the ./manual-typings/ folder. For example, the lodash.throttle

module can be defined in the ./manual-typings/lodash.throttle.js file as follows.

declare module 'lodash.throttle' {

declare var exports: any

}Here, I’m being lazy with the types and simply declared the default export as any, which means it will not be type checked.

Using the any type for module declaration is a good starting point for your project, and you can always go back to define

the correct types when you have the time to.

// Better definition

declare module 'lodash.throttle' {

declare type ThrottleOptions = {

leading?: boolean,

trailing?: boolean

}

declare var exports: (fn: Function, wait?: number, options?: ThrottleOptions) => void

}Wrapping Up

So should you start using types in your projects? It is really up to you! If you do choose to start using types though, you will find that your application becomes easier to maintain because:

-

The type checker will catch type mismatches for you, resulting in less bugs in production.

-

It will be easier to read existing code, because it will be immediately obvious what the valid inputs and outputs are.

It is also seemless to integrate types into your application through Flow (or TypeScript). For even more powerful type systems in the front end, you can also check out Elm and PureScript – both of which are in the ML family of languages.